“We have a friar and a half!” rejoices Teresa of Avila after recruiting the first two monks to join her reform of the Carmelite religious order—an effort to return Carmelite monasteries and convents too their original emphasis on the interior life. The “half” was likely John of the Cross, just under five feet tall and 25 years old.

“We have a friar and a half!” rejoices Teresa of Avila after recruiting the first two monks to join her reform of the Carmelite religious order—an effort to return Carmelite monasteries and convents too their original emphasis on the interior life. The “half” was likely John of the Cross, just under five feet tall and 25 years old.

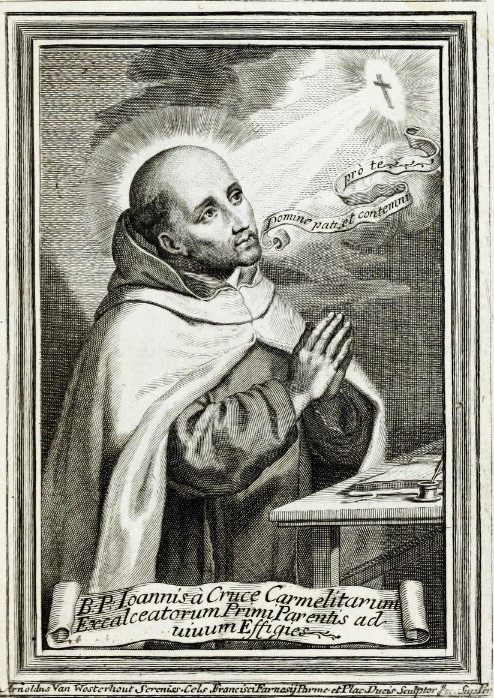

Widely regarded as a saint in his own lifetime, John’s diminutive physical size contrasted greatly with his spiritual stature. Teresa would later describe him as having reached “the greatest height of sanctity human creature can attain to in this life.”

His was an unusual combination of qualities: asceticism, courage, wisdom, intellectual brilliance, discernment, sweetness, compassion, humility—together withal talent for administration and poetry. John is especially noted for his mystical poetry and spiritual commentary. Often regarded as Spain’s finest lyric poet, his soaring lines were born of his own “dark night of the soul.”

An outstanding student and scholar

Exposure to adversity began in John’s childhood. His father’s untimely death left his mother with three sons to support by weaving. (John was the youngest.) Destitute, the family barely scraped out a living.

John’s fortunes began to change at age 14. The administrator at the hospital where he worked as an orderly arranged for him to continue his studies, and John’s great gifts of mind and spirit quickly gained recognition.

After joining the Carmelite Order in 1563, he was steered away from the humble friar’s life he desired and sent to the University of Salamanca to study for the priesthood. An outstanding scholar, John taught classes while still a student.

Yearning for a life of solitude

By 1567, however, the year of his ordination as a priest, John was in crisis. Longing to devote himself to a life of prayer and meditation, he was on the verge of leaving the Carmelite Order when he met Teresa of Avila.

Teresa had launched the Carmelite reform movement five years earlier, in 1562. Having founded several Reform convents for Carmelite nuns, she convinced John that he could assuage his thirst for a deeper spiritual life by becoming one of the first monks of the Reform.

Shortly afterwards, in a tumbledown shack in the remote hamlet of Duruelo, John established the first house of the Reformed Fathers. There he and his companions spent long hours in prayer and meditation, and also visited the nearby villages to minister to the people.

It was the life John had yearned for, but it was not to last. He was destined for a leadership role in the reform of the Carmelite Order, and a life of intense activity.

“Saints are too human to be scandalized!”

In 1572, Teresa was asked to bring the Reform to her old Convent of the Incarnation in Avila. She summoned John to help her by becoming the convent’s spiritual director and father confessor.

John had a gift for guiding others. Gently, yet without compromise, he was able to show people their own unique way to go forward in their interior journeys. Among the one hundred and thirty nuns of the Incarnation, he had ample opportunity to exercise that gift.

Some of the nuns were either awed or intimidated by John’s asceticism and detachment, but as they came to know him, they often loved him for his warmth, humility, and understanding of human nature. One young nun, fearing to come to him for confession because of his saintly reputation, received John’s assurance that not only wasn’t he a saint but had he been, there’d be still less reason to fear because “saints are too human to be scandalized!”

John was most compassionate toward those suffering spiritual dryness or depression in what he later called the “dark night of the soul.” He gave them the encouragement that God loved them and was simply drawing them deeper in faith through their trials. Often he would write on a slip of paper a few words, chosen especially for them, to reflect on.

Kidnapped and imprisoned

While living in Avila, John received his greatest test of endurance. As the Reform effort gained momentum, Carmelites opposed to the Reform intensified their efforts to undermine it.

In December of 1577, John was kidnapped by opponents of the Reform, taken to Toledo, and imprisoned in a tiny cell with no furnishings, little light, extreme temperatures, and bread and water his only nourishment.

There he languished for nine months. Three times a week the monks scourged his bare shoulders in their attempts to turn him away from the Reform. All this the emaciated prisoner bore without a word, exasperating his captors by his refusal to break his silence.

He spoke only to God, and out of the depths of his isolation, deprivation, and physical suffering he began to experience wonderful closeness tithe Divine. Flooded with divine love, he composed and committed to memory the soaring lines oaf poem about the soul’s union with God that would later become The Spiritual Canticle.

Though close to death, he had no thought of escape until the Virgin Mary ordered him to flee and led him through a labyrinth of hazards. In the dead of night, John unscrewed his door lock, stole past the guard, slid down from a window on braided blanket strips, climbed another wall, and leapt to freedom.

At the break of dawn, he finally reached a Carmelite convent where the nuns gave him refuge and arranged for his treatment (in secrecy) at a nearby hospital. Before departing, John told the nuns of the divine love that had flooded his soul during his ordeal and of his deep gratitude toward his tormentors.

A whirlwind of activities

When the conflict with the Reform’s opponents was temporarily resolved, John set out to spread the Reform across Spain and was plunged into a whirlwind of activities.

Sometimes traveling with Teresa, he founded new monasteries and convents; gave support to those already established; dealt constantly with administrative matters; directed the studies for Carmelite students in the university town of Baeza; and had a growing ministry that embraced not only monks and nuns but also lay people. He also completed his four major prose works.

After Teresa’s death in 1582, John shouldered the full responsibility of continuing the Reform. One day, realizing that there was one thing to which he was still attached, he took out his bag of letters from Teresa and burned them all.

In 1588, John had a vision of Christ in which Jesus asked him what he desired. John replied, “Lord, give me trials to suffer for You that I may be despised and held in no account.” Though John had already suffered trials aplenty, his wish would soon be fulfilled.

Dissension within the Reform

With Teresa gone, dissension arose within the Reform itself. John’s courage and forthrightness in upholding Teresa’s vision led to his removal from his various offices and his assignment to one of the poorest monasteries. There John lived as a simple monk gathering chickpeas in the garden, and found more time for prayer and meditation.

Meanwhile, John’s self-styled enemies within the Reform mounted a smear campaign to disgrace him. One of his brother monks, hoping to get him expelled from the Order, went around the monasteries seeking defamatory information. The campaign proved unsuccessful, but some of John’s spiritual brothers, concerned frothier own reputations, began to pull away.

When John fell sick and needed to be moved closer to medical treatment, he was given a choice of going to Baeza, where he had many friends or to Ubeda. He said: “Take me to Ubeda rather than Baeza.” Sensing that death was near, John wanted to end his life in obscurity.

“This is all God’s doing”

The superior of the monastery at Ubeda received John coldly, assigned him one of the poorest rooms, and denied him visitors and adequate medical care. “This is all God’s doing,” John said calmly amidst great physical suffering. A few months before his death he wrote a brother monk: “Where you don’t find love, put love and you will find love.”

Eventually, John’s calm acceptance of his circumstances won over the superior. John died December 14, 1591 at age 49. On news of his death, crowds of the poor flocked to view his body and kiss his hands and feet.

One of John’s best-known poems beautifully describes those qualities of humility and selflessness that were the hallmark of his life and the source of his ever-deepening joy:

In order to arrive at having pleasure

in everything,

Desire pleasure in nothing.

In order to arrive at possessing

everything,

Desire to possess nothing.

In order to arrive at being everything,

Desire to be nothing.

In order to arrive at the knowledge

of everything,

Desire to know nothing.

John’s body remained incorrupt for many years and he was canonized a saint in 1726.

Patricia Kirby, a writer and educator, joined Ananda in 2002, residing first at Ananda Village and now at Ananda India.

3 Comments

Thank you pat for this beautifully constructed summary of Saint John of the Cross’ life. Deeply inspiring, engulfing me in the vibration of Divine Love just before retiring to bed. Hope you are fine

Love, Renata

John of the Cross could perfectly have been Yogananda.

Thank you