When you feel stressed out, easily angered or anxious, even depressed, and hear that meditation or a retreat can help, do you wonder if the benefits of meditation are real?

A study by the University of California at Davis published this year in the Journal of Cognitive Enhancement shows that regular meditators going on an intensive meditation retreat were better able to focus and cope with stress, were less emotionally reactive, and felt happier immediately after the retreat. For those who continued daily meditation practice, the benefits continued seven years later.

Even though the gains fell off as the meditation practice fell off, the fact that positive effects were still notable demonstrates it’s worth going on a meditation retreat.

The ancient Yoga masters and Buddhist monks were right!

The people in this study meditated intensively (about 6 hours every day) for three months in retreat. While encouraging, most of us are not monks. We don’t see ourselves retreating that far or permanently from the world. We have people and commitments that we care about. This is our world to be in, no matter how challenging it gets.

So how can meditation and retreats help relieve stress reactions when you are going to drop right back into the machine that seems to be chewing you up?

Meditation Shapes Your Brain—for the better

Scientists around the world have turned your natural skepticism into over 60,000 research studies, and results are in: the ancient Yoga masters and Buddhist monks were right!

Studies today show how meditation affects chemical reactions in our brains to mitigate stress reactions, change habits, make you happier, more creative and resilient to change.

Today, doctors are using the study results to select meditation techniques—instead of prescription drugs—to treat anxiety, anger, depression, obsessions, alcohol addiction, inflammation, attention deficit disorders, and help traumatic brain injuries.

Dr. Peter Van Houten M.D. at the Sierra Family Health Center teaches meditation to his patients as a therapy. The science is so supportive that the Health Center received a $200,000 grant to integrate meditation throughout the clinical practice.

Dr. Peter Van Houten explaining the neuroplasticity of the human brain.

If meditation is sounding like a panacea again and you’re feeling skeptical, let’s get into how the brain works. This is where the science is getting super cool. Studies now show how meditation releases specific chemicals in distinct sections of your brain and how meditation can produce the most beneficial dosages of those chemicals to support the behaviors of the person you want to be.

Neuroscience: How Your Brain Works

You’ve heard of the amygdala. It’s most accurately called the “Threat Detection Center,” as Dr. Joseph LeDoux, PhD explains in Psychology Today. Your amygdala detects and responds to sensations—could be an event, an idea, a comment—and triggers the secretion of chemicals throughout your brain and body to say that something important is happening.

What you do with that sensation is a separate step; one that we could call a feeling, like pain, fear, pleasure, or nothing at all. The point is, you have a choice.

The amygdala works with the insula, the part of the brain that monitors bodily sensations to figure out how strongly you are going to respond to a sensation. The insula gives you “gut feelings.” It also helps you feel empathy and achieve harmony with people.

We’ve had the idea that our brains are hard-wired, especially with reactions like the fight-or-flight response. Modern neuroscience is teaching us how changeable our brains really are.

Who do you want to be in six months?

Neuroplasticity: Your brain can and does create new neural connections throughout your life. Science is proving precisely how ancient meditation techniques are tools to shape your brain.

Dr. Van Houten asks his patients: “Who do you want to be in 6 months? The truth is you will be a slightly different version of yourself. Do you want to guide that process so that you’re working toward someone you would like to be?”

Often called the “Assessment” or “Executive” Center of your brain, the prefrontal cortex is the part of your brain that helps you assess situations and information in a more logical, rational, balanced way.

The lateral prefrontal cortex modulates your emotional responses from threat detection. This dampening effect can diminish your automatic reactions—self-talk, long-held beliefs, and habits.

Commonly called the “Me Center,” the medial prefrontal cortex compares everything to you, your perspective, and experiences. It processes information when you are being social, inferring what other people are thinking or feeling as well as when you are daydreaming, considering the future, and reflecting on yourself.

The Me Center actually has two sections. Each section pays attention to one part of the empathy equation: who you view as similar to you and who you perceive as different from you.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex processes information related to you and people that you view as similar to you. “This is the part of the brain that can cause you to end up taking things too personally,” says Dr. Rebecca Gladding in the book, You Are Not Your Brain. This part of your brain tends to cause rigid mental attitudes, rumination, and worry that can exacerbate anxiety or depressive thoughts and feelings.

The dorsomedial prefrontal cortex processes information related to people whom you perceive as being dissimilar from you. This part of your brain is involved in feeling empathy, especially for people whom you perceive as different. It helps you build and maintain social connections.

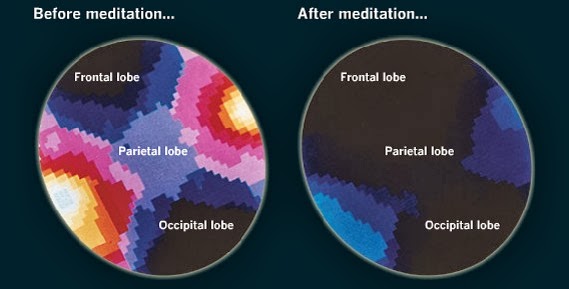

Examining the Brain of a Meditator

When scientists look at the brains of people who do not meditate, they typically see strong neural connections within the Me Center and between the Me Center and the Threat Detection center. As the Me Center dominates processing of sensations from the Threat Center, you tend to feel more threats and get stuck in mental loops.

The Me Center dominates because the Assessment Center’s connection to the Me Center is relatively weak. When the Assessment Center works at a higher capacity, it modulates the excessive activity focused on “my thoughts/feelings/experiences” and tries to interpret what you think another person is thinking/feeling—overthinking, ruminating, taking things personally, and projecting. The Me Center runs amok.

How Does Meditation Work?

This is a complex question, mostly because meditation is not one thing. There are many types of meditation that offer distinct benefits and research is beginning to tease out the differences for therapeutic purposes. Meditation can generally be split into two groups: watching the breath (mindfulness) and focusing the breath (pranayama).

Meditation trains the brain to achieve sustained focusWhen you meditate on a regular basis, you can short-circuit the unhelpful activity of the Me Center and boost power to your Assessment Center. Meditation weakens the connections between your Threat Center and your Me Center so that your executive functions can be in control.

Many studies have proven that this change in your brain can effectively treat depression instead of drugs. Dr. John W. Denniger at the Harvard-Massachusetts General Hospital explains how:

Meditation trains the brain to achieve sustained focus, and to return to that focus when negative thinking, emotions, and physical sensations intrude—which happens a lot when you feel stressed and anxious.

Meditation Is a Brain Fertilizer

Researchers at the Institute of Neuroscience at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland proved for the first time that ancient yoga and meditative breathing techniques directly affect the levels of a natural chemical messenger in the brain called noradrenaline.

Noradrenaline is an all-purpose action system in the brain. When we are stressed, we produce too much noradrenaline and we can’t focus,” explains Michael Melnychuk, PhD candidate at the Trinity College. “When we feel sluggish, we produce too little and again, we can’t focus. There is a sweet spot of noradrenaline in which our emotions, thinking, and memory are much clearer.

When produced at the right levels, noradrenaline helps the brain grow new connections, “like a brain fertilizer.” How you breathe, in other words, directly affects the chemistry of your brain, enhancing your attention and improving your brain health.

Published in Psychophysiology, their research also compared the two traditional types of breath-focused meditation—mindfulness techniques and pranayama techniques—and found that both practices are effective “to [effect] changes in arousal, attention, and emotional control.”

It is very exciting to see that science is finally able to help us understand what ancient wisdom has been telling us for thousands of years.

Practice Kriya Yoga deeply until your breath becomes mind

“Practice Kriya Yoga deeply until your breath becomes mind,” said Paramhansa Yogananda, the yoga master who brought meditation and yoga to America, and wrote the classic best-seller, Autobiography of a Yogi, in which he describes the benefits of the ancient meditation technique, Kriya Yoga.

Meditation Enhances Creativity and May Help Curb Suicide

In a peer-reviewed study called “Mind the Trap,” researchers Reiner and Meiren looked at “mental rigidity,” an effect of your Me Center holding your mind hostage, and causing a whole host of concerns from doctors misdiagnosing patients to suicide.

Research shows that when physicians look at a patient’s case that does not match their experience, they are likely not to see the correct diagnosis.

“Mental rigidity” could also be called ruminating or obsessing, and plays a role in suicide, depression, alcohol dependence, compulsive disorders, and Attention Deficit Disorder. It happens when your Me Center is over-active with your Threat Center.

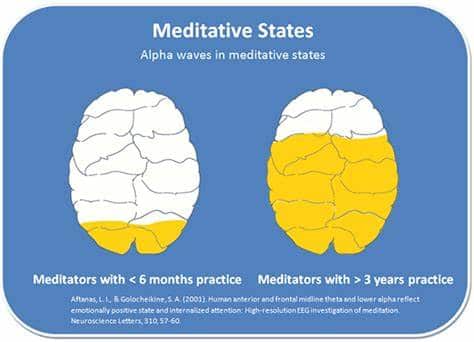

Reiner and Meiren compared long-time meditators (for 3 years, averaging 3.32 hours per week) with people interested in meditation but had not started.

The study concluded that meditators were less likely to be “blinded” by their experiences and “to overlook novel or adaptive ideas.”

In other words, meditation makes you better at recognizing your options and seeing creative, simpler solutions.

Transformation of Being

In their book, Altered Traits, Daniel Goleman and Richard J. Davidson explored the 60,000 studies conducted over the last few decades to understand how the ancient yogic practices of meditation work in your brain.

A psychologist and a neuroscientist, Goleman and Davidson did the first brain scans of Buddhist monks. They gave us “emotional intelligence” and brought “affective neuroscience” into the mainstream.

With Altered Traits, they went on a hunt for “who you become” from dedicated practice. We’ve all experienced an “altered state,” a temporary state of awareness that fades when you’re no longer doing a particular activity.

An altered trait, on the other hand, is a lasting change. Through meditation, you can cultivate an altered state and improve your daily activity. With regular practice, the altered state becomes your altered trait, a transformation of being.

Olympic-level meditators, those who have practiced for more than 62,000 hours, achieve a constant state of meditation rather than a sudden shift in brain chemistry. They’re able to maintain that state, despite significant external events and stimulus.

The findings on the Olympic meditators relationship with pain is one of the most compelling. It demonstrates the diminished impact of the Threat Center on the Me Center, and the strength of the prefrontal cortex in exerting executive control over how information and sensations are interpreted.

In the laboratory, the meditating monks were touched with a hot test tube while monitored for physiological and emotional responses. When they were told that they would receive the touch of a hot test tube, they had no emotional response. Most of us would immediately start feeling pain before it begins, like hearing the sound of a dentist drill.

When the monks actually felt the hot test tube, the physiological response registered but the monks registered no emotional reaction. The Olympic meditators demonstrate that you can utilize the natural neuroplasticity of your brain to change a common stress reaction to an outside stimulus.

Maybe you’ll still get Novocain for a root canal but you can see how having a healthier connection between your Threat Center, your Assessment Center, and your Me Center could reduce your anxiety, and help you to remain calm in the face of an upset boss or teenager.

You can do this with less than 20 minutes a day

A final benefit of meditation—a gift from you to the world—is that you become more empathetic. Meditation strengthens the helpful part of your Me Center and its connections with the empathetic part of your Threat Center. You become better able to understand where another person is coming from, especially those you perceive as different from you.

Wow! Wouldn’t the world be a better place if we would all enhance our ability to feel empathy and compassion for everyone?

“You can do this with less than 20 minutes a day,” says Dr. Shanti Rubenstone M.D., who graduated from and taught at Stanford University Medical Center. She specialized in treating chemical dependency and now practices “transformational medicine” in Mountain View, CA.

Dr. Van Houten agreed when they spoke in the Science Behind Meditation Symposium (you can watch his video free). “The cumulative positive effects begin to show up at 12-15 minutes of meditation per day.”

We can expect long healthy lives with regular meditation

So how do you start a meditation practice that you can maintain? Today, there are many ways: through apps, online courses, at a yoga or meditation studio, or going to a meditation retreat. Giving yourself a good teacher and time to support this new habit taking hold is essential.

“We can expect long healthy lives with regular meditation, for all of us and for the future of human kind.” –Dr. Peter Van Houten M.D

6 Comments

Excellent article, Vandana, thanks!

Hi

I suffer from Essential Tremors that are triggered due to misfiring in the Thalamus region of the brain. Is there any specific meditation techniques I can use?

I currently meditate for 45 to 50 minutes everyday for the past 3 months

We reached out to get some answers for you

and received a response from Jayadev, one of our

Ananda Yoga instructors who suggests that

cooling the nervous system would be advisable:

Gentle yoga postures with deep slow breathing

(hare pose or other inversions) that bring blood

and prana to the brain – but, of course, be sure to confer with

your physician.

Consider using deep, calm, slow breathing in Savasana

as it might be helpful in calming the tremors and nervous reaction.

Also, cooling pranayama such as Chandra Bedha

pranayama or just simple, deep even-breathing.

Environment is also critically important – be in nature where you can

breathe and relax and avoid anything agitating. Consume cooling foods

as well such as fruit.

We hope you find some relief. Blessings.

Thanks for this detailed synthesis! I’m involved with a community of college and university teachers who are teaching students about the world’s daunting problems and the journey toward sustainable solutions. We are finding that contemplative practices–both in and out of class–can help students understand the complexity of these issues, but more importantly, they can help students cope with the emotional undertow of worry and despair. Empathy plays a critical role here…

On Rest, Mindfulness, and Affective Neuroscience

Presented here for your consideration is a new and quite radical explanation of mindfulness from the perspective of affective neuroscience, or more specifically, a neurologically grounded theory of incentive motivation. The explanation is simple, easily falsifiable, and its procedural entailment redefines the practice of mindfulness. Still, it may be wrong. Indeed, a bad theory must not overstay its welcome, and although I provide a granular explanation of my hypothesis in my treatise and journal article linked below, it is procedure that determines its validity and worth, the ease and simplicity of which will enable you prove or disprove my argument within minutes.

————————————————-

In 1984, the psychologist David Holmes published in the journal ‘The American Psychologist’ a review (linked below) of the cumulative research on meditation and concluded that meditative states were merely resting. The article was roundly criticized, as meditation was obviously much more than a simple state of rest. Well, the critics were half right, meditation is rest, but rest is NOT simple. Indeed, rest induces a pleasurable or affective state which can be modulated in turn by the moment to moment expectancies that tell you where you are and where you are going. Indeed, contrary to what mindfulness suggests, being in the moment is impossible, for we must always consciously or non-consciously decide upon the direction or meaning of our actions from moment to moment, and this translates into effective and affective outcomes. These concepts can easily be anchored to the facts of behavior and translated into simple validating procedure, as I argue below.

In affective neuroscience, incentives embody affective states that reflect attentive arousal as mediated by dopamine systems, and pleasure, as mediated by opioid systems. The nerve cells or nuclei of both systems are proximally located in the mid-brain and can activate each other. For example, looking forward to a pleasure accentuates the pleasure, and a pleasurable experience perks up attentive arousal. In addition, opioid and dopamine release scales with the intensity or salience of the eliciting stimulus, as pleasure rises with tastier foods, and attentive arousal spikes when we view an unexpected vista or challenge.

Dopamine release can occur as a phasic or intermittent response, as when our attention ebbs and flows as a function or our momentary fluctuating interest and boredom. It also occurs as a tonic or sustained response in order to maintain a baseline level of alertness that allows us to go about our lives. Similarly, opioid release occurs as a phasic response when we sample our daily pleasures, and it also may be a tonic response, but only when the covert musculature is in an inactive or relaxed state. When an individual is tense or anxious, tonic opioid activity is suppressed. This makes evolutionary sense, as resting conserves an animal’s caloric resources, and animals in the wild sustain their survivability through the dual incentive of alertness for predators while at a pleasurable state of rest. (as your lounging cat would attest, if it could speak)

From these facts, certain predictions about behavior may be made that conform with empiric reality. For example, peak or flow experiences that reflect heightened attentive arousal and pleasure only occur when an individual is both relaxed and is aroused by behavior that entails highly positive moment to moment meaningful outcomes (e.g. creativity, sporting events). Dopamine in turn stimulates opioid activity, and the enhanced dopamine/opioid interaction results in an ecstatic or peak experience.

This observation can also be practically confirmed (or falsified!). Simply elicit a resting state through a mindfulness procedure and continuously couple it with imminent behavior that has important or meaningful outcomes, and the more meaningful, the greater the affect. The underscores the fact that as a resting protocol, mindfulness will elicit a pleasurable state which will scale with the salience of momentary outcomes that in turn can be easily arranged. Mindfulness in other words is not a steady affective state, but a variable affective state, and can be a mystical or peak experience, or just a mildly pleasant way of chilling out. It all depends upon what you are looking forward to imminently do.

For a more detailed explanation see pp.47-52, 82-86 on the linked treatise on the psychology of rest.

Holmes Article

https://www.scribd.com/document/291558160/Holmes-Meditation-and-Rest-The-American-Psychologist

Meditation and Rest

from the International Journal of Stress Management, by this author

https://www.scribd.com/doc/121345732/Relaxation-and-Muscular-Tension-A-bio-behavioristic-explanation

The Psychology of Rest

https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/9bba72_a06875c1cef541c5a7e55bac9ef86711.pdf

and at doctormezmer.com

Cheers!

AJMarr

New Orleans

Thank you so much Vandana for this very informative and well-written article! Extremely grateful…