Does this feel familiar?—You’ve been teaching a group of students for a while, and you’re seeing signs that they’re bored with the “same old poses.” One or two of them might even have said so, or lobbied for more advanced poses. What should you do?

All of us have experienced this to some degree, but when I read David (Uddhava) Ramsden’s excellent article on it —and when a few other teachers recently lamented facing similar challenges— I decided to address it in this column.

The Root of the Issue

Paramhansa Yogananda used to marvel at how Americans love change. Coming from tradition-steeped India, he found it strange to see a culture that changes jobs, houses, cities, spouses, and yes, gurus, at the drop of a hat. I think it’s safe to say that, in the years since then, that love of change has grown even stronger. “New” has become nearly synonymous with “better.” (If you doubt that, simply look at advertisements and product packaging. The advertising industry has spent a lot of money to acquire this knowledge, and they spend even more taking advantage of it.)

Certainly openness to change is good—even vital, for it helps us let go when we need to let go, rather than clinging to the past. But when we grow addicted to change, wanting change merely for the sake of change, it is dysfunctional. It fosters restlessness, inability to focus—and without focus, we’ll get nowhere in life. Deluded into thinking that variety of experience is more important than depth, we perpetually skim the surface of our lives, never going beyond superficial achievement or enjoyment.

This is a universal human condition, not just an American condition (although, typically, Americans may be the most extreme). In the forthcoming book, God Is for Everyone, (Swami Kriyananda’s rewrite of The Science of Religion, which was originally ghostwritten from Paramhansa Yogananda’s outline), Yogananda observes: “Because human beings are habitually restless, they feel attracted to complexity and shun divine simplicity. They embellish with egogratifying variations the pristine melodies of the soul.”

Is it any wonder, then, if at times our students become bored? What can we do about it?

What Not to Do

Ananda Yoga teachers aren’t the only ones who face the boredom challenge. In fact, teachers who don’t know how to take students inward face a much tougher challenge than we do, because as long as students remain merely on the physical level, boredom is inevitable. Over the last 5–10 years, I’ve noticed yoga teachers gravitating toward “solutions” that I don’t believe serve their students.

Some teachers actually cater to restlessness: “new is better.” As they run out of techniques from their own traditions, they desperately look to other traditions for more. No matter that their students never go deep into anything—at least they’re being entertained as their addiction to change gets strengthened. (It also creates trouble for the teachers: sooner or later, they run out of new things to teach. What then? Get a whole new crop of students?)

Quite apart from the fact that this eclectic approach has no power—for reasons I’ve shared before—I recall Swami Kriyananda’s common-sense advice: “Stay with what students will actually practice.” New or unusual techniques may titillate students’ curiosity, and students will be glad to learn them, but they won’t do any good if the students get confused or won’t practice them—or more likely, both.

Worse yet, some teachers introduce more-advanced poses to students who are not ready. Why? To wow them? To capitulate to student demand? I read recently of a beginning series in which headstand is taught in the first or second session. That’s crazy and dangerous! And again, if students aren’t yet able to practice poses safely and/or effectively, why teach such poses to them in the first place?

Certainly there is a time for more-advanced poses (I’ll address that later), but when you know in your heart that the time hasn’t yet come for the student(s) and poses(s) in question, then dharma demands that you say, “Not yet.” I salute all teachers with the courage and integrity to resist this temptation—even in the face of possibly losing students to another teacher who will give them what they want.

Look at the Big Picture

So, does this mean that we should always teach the same poses, hoping that somehow students will learn to go deep? Obviously not. But we do need to take a larger perspective.

First, remember that we, as teachers, are a crucial part of this process. It’s not merely about which techniques we know how to teach; it’s about the vibration that we bring into the classroom. We need to make sure that we are inspired, creative, and able to give whatever needs to be given. Without that, we cannot succeed as teachers.

Second, we need to understand how to teach new things to our students. Here I mean, not only how to do a new pose, but how to teach new and old in such a way as to bring students toward a better understanding of their yoga practice. This means both broadening and deepening their experience of yoga.

Now I’ll offer some specific strategies in both of these arenas. Certainly every circumstance is unique—your knowledge and skills, your students’ abilities and level of experience, the type of classes you teach, your personal obligations outside of your teaching, your willingness to take risks, etc.— so there’s no one-size-fits-all strategy. Nevertheless, there are many points to make and possibilities to explore.

First Things First: Take Care of the Teacher

It all begins with you. Your classes will feel fresh and alive if—and only if—you feel fresh and alive. When you teach creatively and magnetically, your students will not be bored, no matter what you do. Creativity and magnetism come from feeding yourself spiritually and staying inspired. So ask yourself, “Am I feeling the inspiration I once felt?” If your answer is, “No,” then do whatever it takes to become inspired.

For example, are you so swamped in your teaching and other obligations that your private sadhana has slipped? Then you know your first priority: let go of what Paramhansa Yogananda called the “unnecessary necessities” of your life, and restart your sadhana.

Have you stopped journaling or reading inspiring books or whatever other inspirational activity has fed you in the past? If so, rearrange your priorities to start again, even if only a little bit.

Do you spend time with people who inspire you? If not, find a way. Remember Yogananda’s words, “Environment is stronger than willpower,” and fashion a supportive environment for yourself and for others. For a yoga teacher, this should not be difficult. (See my article in the last issue for suggestions.)

And speaking of environments, how long has it been since you visited The Expanding Light? If you want inspiration for teaching Ananda Yoga, what better environment could there be? Come in whatever way inspires you—for Level 2 training, or Personal Retreat, or Yoga in Action, or whatever appeals to you—but come. (Remember: there are financial aid opportunities for most Level 2 programs.)

So you’re the #1 priority here. It’s not selfishness—it’s about giving your best to your students. If you’re not going to take care of yourself, anything you do outwardly to enliven your classes will have at most a fleeting benefit—and you might as well stop reading this article right now.

Give Students “Something More”

Still with me? Great. Now let’s talk about specific strategies for keeping your students interested and engaged.

I want to begin with another word about newness: there’s nothing wrong with it. On the contrary, newness is inherent to the process of learning. But it needs to be newness in the sense of discovery, not mere novelty or distraction. If we can give our students an experience of discovery and foster their desire for more—whether we are teaching new poses or familiar poses, or even no poses at all—then they will learn how to work constructively with their innate human restlessness rather than merely indulging it. Then we will really be teaching yoga, and students will always be hungry for more.

Swami Kriyananda puts it this way: in teaching Ananda Yoga, we need to let students know that there is always something more for them, a higher level to reach for, if they are interested in pursuing it. This means not merely telling students that there’s more, or loading them with techniques that they cannot or will not practice, but showing them through their own experience that there is something more inside of them.

Yes, this is challenging, but it is also a great opportunity to be creative with our teaching—and when we’re creative, we too get recharged. I’ll now describe a few of the ways in which we can foster our students’ spirit of discovery. Whether they’re new or familiar, I hope they will spark creative thoughts in you.

Back to Basics

One way to spark renewed interest in familiar asanas is to offer special focal points for asanas, new territory to explore. How? One possibility is to go back to basics, emphasizing building blocks of poses. It’s remarkable how, in their hurry to do more and more poses, students forget important foundational aspects, and their practice bogs down.

For example, you might take an “asana of the week” approach: focus on a particular asana, break it down in detail, emphasize specific aspects of it, repeat it several times with different emphases each time, really getting intimate with the pose. Have students do it mentally as well as physically. Take time to discuss the affirmation with your students, guiding them (or helping them guide each other) to a deeper understanding of how it can “complete” their practice of the asana. Encourage them to make the affirmation visual and feeling-oriented, not just verbal, so their experience will be fuller.

In fact, how about doing your version of the “drawing class” from AYTT, having students draw a picture of their experience in the pose and create their own affirmation? It’s a great exercise for teaching students how to go deeper in their experience of any asana—and crayons are cheap. (I’ll be happy to e-mail you an outline of how to do this.)

Of course, in an “asana of the week” approach, you’d do other asanas as well, but you’d give the bulk of your time to just a few asanas. This approach can even help turn an asana from a nemesis into a friend.

New Tricks for Old Downward Dogs

Here’s another approach: explore asana variations that give new emphases—and new life—to the physical dimension (and hence the energetic dimension) of a pose.

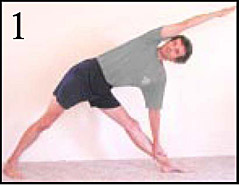

Consider, for example, trikonasana. In AYTT, we teach it in a way that suits beginners, but there are many variations that highlight different aspects of the pose.

You could bring the top arm’s biceps down alongside your ear, parallel to your spine instead of vertical; then stretch through the crown of the head, toward that hand, and stretch the bottom sitbone away from that hand (Figure 1). This is helpful for getting more length in the spine and a deeper crease in the leading hip, helping students stay naturally open through the underside of the rib cage. After holding this variation of a number of breaths, bring the arm back to vertical. Now the opening that students experience in the basic pose will likely feel much more dynamic because their spines are much more open.

Or use the wall to deepen the hip crease and create more openness: Stand away from the wall and perpendicular to it, positioning yourself so that when you come into the pose, your lower arm can stretch out to the side and slightly up, resting on the wall (Figure 2). As you hold the pose, press into the wall to help move the lower sitbone away from the wall, deepening the hip crease and enabling you to come farther into the pose without closing off the underside of the rib cage.

Another way to foster openness is to wrap the top arm behind your back, with your fingers on the inner thigh of the leading leg (Figure 3). (A strap around the thigh will work for those who cannot reach the inner thigh—see Figure 4.) Draw the hand (or pull the strap) back to help you rotate open through the pelvis and torso without compromising the leading leg’s knee alignment. Be sure to keep the focus in the pelvic region—there is a tendency to use this variation simply to open the shoulders further, which adds nothing to the pose if the chest is already facing straight ahead.

Or use a wall to help maintain knee alignment: Stand with the leading leg’s outer thigh and buttock against the wall. Draw the trailing pelvic rim toward the wall to open the pelvis without losing leg contact with the wall. After coming into the pose, bring the top hand down to the trailing pelvic rim and again draw it toward the wall, fostering more openness. Be careful not to compromise knee alignment: keep the leading outer thigh and buttock pressed against the wall, and adjust the trailing leg and foot as needed.

Or lengthen both arms overhead, in line with the spine (Figure 5). This challenging position teaches students to engage their leg and trunk muscles more, giving the pose a stronger foundation and allowing students to give over more of the upper body to the opening/receiving process that is the heart of the pose.

Compare, Contrast, Discuss

One key to kindling students’ interest is to help them experience and enhance the “feeling” of a pose, the state of consciousness toward which the pose moves us. Once they realize that they can bring their mind into dynamic partnership with the body to lift their awareness, they will never be bored with that pose again. And they’ll eagerly seek the same experience with other poses.

This isn’t always easy to teach, but one way is to have students do a pose in two or more different ways, and discuss how the experience of the pose changes. For example, try different entries into an asana as a way to understand the pose more deeply, and invite your students to share their experiences.

Consider chandrasana. In AYTT, we teach a very simple two-breath entry that’s straightforward for beginners. Someone who knows the pose, however, is likely to prefer entering on just one breath: inhale up, exhale to the side. Better still, someone with good body awareness can do the entire entry on the inhalation alone: inhale up and over to the side, just as one would inhale up and back when entering a backward bend. Yes, lots of parts moving are simultaneously, but those who can maintain their alignment will feel much more “strength and courage” filling their body cells. Try it with your experienced students, and invite discussion.

Or, try entering dhanurasana or setu bandhasana in two different ways: once on an inhalation, as we teach in AYTT, then on an exhalation. Invite students to notice the difference. The second way makes it easier to keep the pelvis tucked—at the expense, perhaps, of some of the vitality, openness, and spinal length that come with entering on an inhalation. Then have them enter the pose again, on an inhalation this time, but resolutely maintaining the spinal/pelvic alignment that came from entering on an exhalation. Then have the students discuss their experiences. Chances are they’ll now have a better idea of how to enter on an inhalation, reaping all the benefits of that approach, without compromising the spine.

Want something even simpler? Try virabhadrasana with palms down vs. palms up. Or utkatasana with palms down vs. palms up. Or utkatasana holding the breath as you crouch into phase 1 vs. exhaling into phase 1. Or salabhasana (arms overhead version) with palms down vs. palms facing each other. Again, invite discussion. Little things like this can really help students understand poses from their own experience.

Here’s one of my favorite ways to help students tune in: compare the standing backward bend with what Iyengar folks call “warrior 1.” (In case it’s new to you, this pose is like standing backward bend with a very wide stance and a somewhat different arm position. However, I ask students to hold the arms as for standing backward bend, in order to make the comparison clearer.)

First, I have them do warrior 1 on both sides. I don’t talk about a lot of alignment details; I just make sure they know what they’re doing. I ask them to feel the general essence of the pose and notice how it affects their energy or state of mind. Then I have them do standing backward bend on both sides, offering exactly the same (minimal) guidance. Then I ask them about the differences. Usually, I’ll see light bulbs going on all over the room: “I get it—this pose is about this, and that one is about that!”

Somehow it’s often easier to feel the essence of a pose by comparing it with a similar pose. Then students begin to understand better why one might use one pose or the other, and how exactly to tune in to the essence of the pose. (In this particular case, it also invariably deepens their appreciation for the “simple” standing backward bend.)

These are just a few ideas; I’m sure you can think of others. It’s an effective way to engage your students as you solidify their understanding of what they’re doing and why they’re doing it.

Pranayama

How much emphasis do you give to the pranayama breathing techniques in your classes? If you’re just paying lip service to them, you’re missing a great opportunity to get your students even more interested in yoga practice.

There are many possible places for pranayama practice in an Ananda Yoga routine:

- As a centering at the beginning of your class.

- Right after Energization to focus the awakened energy.

- After the last standing pose to “change gears.”

- After any particularly energizing pose, such as dhanurasana or ustrasana, to focus the energy.

- As part of the deep relaxation, to internalize the mind.

- As the last thing before ending your class.

I feel that the most impactful place is that last location, where the students can practice for a longer time and get deeper into the experience. When they do that, they will be led naturally into a meditative state, and that certainly will pique their interest in deeper practices. (Properly done, a long practice should make students feel like meditating, not doing asanas. That’s why pranayama practice in earlier parts of the routine should be rather short.)

By the way, we thoroughly explore the practice and teaching of pranayama techniques in the Advanced Pranayama Level 2 program. Until then, please note the importance of building a strong foundation of proper technique in normal breathing before trying morecomplicated practices. As with asanas, students too often are eager for the next pranayama technique before they have adequately mastered simpler ones.

In the next issue, we’ll explore teaching advanced asanas.