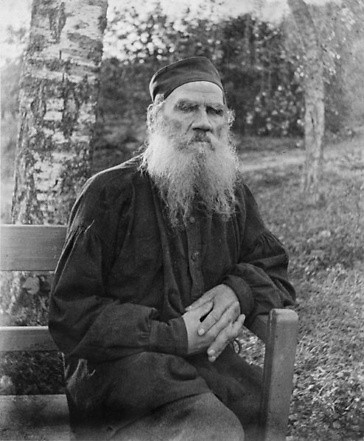

Leo Tolstoy in 1897.

The modern fad is to spend and spend and spend to the limits of our ability, and beyond.

Several centuries ago, the great preacher and evangelist John Wesley (1703-1791) set a radically different example.

Although Wesley was born in humble circumstances, he became so well known that his income eventually exceeded 1400 pounds per year—in today’s terms, the equivalent of about $500,000.

What did John Wesley do with his wealth? Did he tithe it? No. He went a considerable ways beyond tithing. He disciplined himself to live comfortably on 30 pounds per year (about $10,000 in today’s money) and gave away the remaining 98 percent of all he earned.

In the Bible, Jesus says, “I tell you, use worldly wealth to gain friends for yourselves, so that when it is gone you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.”

Wesley preached a sermon on this passage in which he spelled out his philosophy—he considered money a tool that can be used for great good or great ill.

“It is an excellent gift of God, answering the noblest ends. In the hands of His children, it is food for the hungry, drink for the thirsty, raiment for the naked: It gives to the traveler and the stranger where to lay his head. By it we may supply the place of an husband to the widow, and of a father to the fatherless. We maybe a defense for the oppressed, a means of health to the sick, of ease to them that are in pain; it may be as eyes to the blind, as feet to the lame; yea, a lifter up from the gates of death! It is therefore of the highest concern that all who fear God know how to employ this valuable talent; that they be instructed how it may answer these glorious ends, and in the highest degree.”

He shared three principles by which he felt we should live guided for our own benefit: “Gain all you can, save all you can, give all you can.”

On another occasion he remarked, “If I leave behind me ten pounds…you and all mankind [can] bear witness against me that I have lived and died a thief and a robber.”

Wesley’s generosity has a flavor of “spiritual pragmatism”—it isn’t merely for the promise of heavenly gifts that we should give, but because the principle of generosity is woven into the divinely ordained fabric of life.

There was a farmer who grew award-winning corn. Each year he would enter his corn in the state fair, where it would win first prize. A reporter once asked him to reveal the secret of growing first-class corn. The farmer replied that it was simple: he shared his best seed corn with his neighbors.

The reporter was nonplussed: “How can you afford to share your best seed, when your neighbors’ corn is in competition with yours?”

“Why,” said the farmer, “don’t you know? The wind picks up pollen from the ripening corn and swirls it from field to field. If my neighbors grow inferior corn, cross-pollination will steadily degrade the quality of mine. If I am to grow good corn, I must help my neighbors grow good corn.”