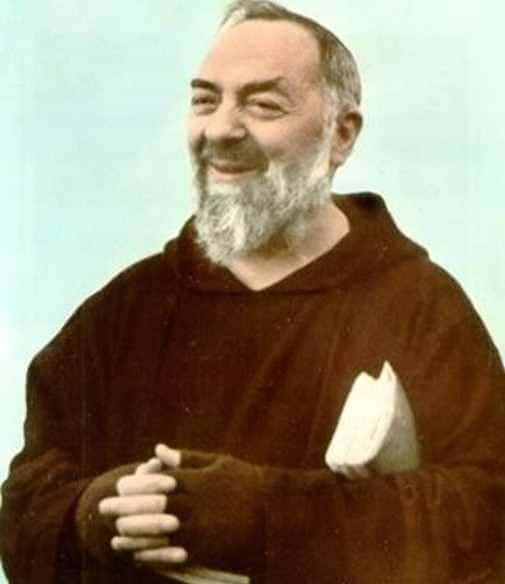

Padre Pio (1887-1968) was an Italian priest and monk whose mission was to instill faith in others during a time of skepticism and unbelief. Although much has been made of Padre Pio’s many miracles, he was dismissive of them, including his well-known ability to bi-locate.

Padre Pio (1887-1968) was an Italian priest and monk whose mission was to instill faith in others during a time of skepticism and unbelief. Although much has been made of Padre Pio’s many miracles, he was dismissive of them, including his well-known ability to bi-locate.

People from all walks of life have testified that it was not Padre Pio’s miracles but his Christ-like presence and deep devotion to God that changed their lives. Through Padre Pio, they experienced the presence of God, or as one person put it—“He made God real.”

Suffering for the salvation of others

Padre Pio dedicated his life to what he called “co-redemption.” For him this meant following the “way of the cross,” whereby great saints suffer for the salvation of others— a view that parallels the Eastern spiritual tradition of taking on the karma of others.

Born Francisco Forgione on May 25, 1887 in Pietrelcina, a small farming community in southern Italy, Padre Pio grew up in a close-knit, religious family and loved going to church and listening to stories of saints. Often he would go off alone to pray and “think about God.”

He would later reveal that from early childhood he regularly spoke with Jesus, Mary, and his guardian angel. In 1902, when he was 15, he became a monk of the Order of Friars Capuchin, which traces back to St. Francis of Assisi, Padre Pio’s patron saint, whom he often saw in vision.

“I want to offer myself”

In 1910, when ordained a priest, Padre Pio decided to offer himself as a victim for the salvation of souls. Writing to his spiritual director, he said:

For some time I have felt the need to offer myself to the Lord as a victim for poor sinners and for souls in Purgatory. This desire has grown continuously in my heart until now it has become a powerful passion.

Though forewarned in visions that demonic forces would try throughout his life to derail this mission, he remained undeterred.

In July 1918, a few days after Pope Benedict XV urged all Christians to pray for an end to World War I, Padre Pio offered himself as a victim for the end of the war. He was then living at Our Lady of Grace friary at San Giovanni Rotundo, a remote, mountainous farming village in southern Italy.

The stigmata appear

A few months later, on the morning of September 20, 1918, while praying in the friary church, Padre Pio received the stigmata—the outward manifestations of Christ’s five wounds. Describing the experience to his spiritual director, he wrote:

All the internal and external senses and even the very faculties of my soul were immersed in indescribable stillness. Suddenly, I saw before me a mysterious person (whom he later identified as the wounded Christ)whose hands and feet were dripping blood….When the vision disappeared, I realized that it was my hands and feet and side that were dripping blood.

The wounds in his hands and feet went straight through—and caused constant pain. They bled unceasingly, emitting the sweet scent of roses and violets. He was unable to close his hands and wore special gloves and shoes, except when saying Mass.

Skeptical doctors subjected him to painful examinations, but the wounds defied medical science. Padre Pio accepted the stigmata as a gift from God for the redemption of mankind, but he would have preferred to suffer in secret, without drawing attention to himself.

To his spiritual children: “pray and meditate”

By now, a circle of “spiritual sons and daughters” had begun to form around him— the beginning of the worldwide prayer groups he would later establish.

To his spiritual children Padre Pio spoke of God’s presence within. He urged them to live in that presence by praying as much as possible, meditating on the life of Christ, surrendering to God’s will, and loving both God and neighbor.

Counseling joy in the service of God, he warned them against the harmful effects of discouragement and worry. Despite his physical trials, Padre Pio’s distinguishing characteristics were joy, serenity, kindness, and humility.

No distance between him and Christ

The Mass was the means by which Padre Pio publicly expressed his oneness with Christ. Eyewitnesses said that he was always in a state of deep inner communion, which uplifted the entire congregation. One eyewitness described it:

The Capuchin’s face, which a few moments before had seemed to me jovial and affable, was literally transfigured…. Fear, joy, sorrow, agony or grief… I could follow the mysterious dialogue on his features. Now he protests, shakes his head in denial and waits for the reply. His entire body was frozen in mute supplication….

Suddenly great tears welled from his eyes, and his shoulders, shaken with crushing weight…. Between him and Christ there was no distance….

Padre Pio’s Mass could last as long as three hours. He re-lived Christ’s crucifixion and prayed for all who had asked for help.

A “surgeon of the soul”

Equally important to Padre Pio’s ministry was the hearing of confessions, sometimes as many as a hundred a day. He “read souls” with unfailing accuracy and knew exactly what to say to each person.

If a person failed to report a serious sin, Padre Pio would invariably point it out by relating all the details of the offense. Because some would respect him only if he shouted, he would shout— though in his heart, as he said, he was smiling.

Those who came to “test” him, or who weren’t prepared to be truthful, he would gruffly send away. To be refused by Padre Pio was such a shock that it changed people’s lives.

The first wave of persecution

By the spring of 1919, news of the stigmata had leaked out. Miraculous cures were reported, and newspapers throughout Italy were publishing articles about Padre Pio.

This new interest in Padre Pio and the influx of pilgrims and donations to his monastery created jealousy among the local clergy. Spreading vicious lies, they insisted that his wounds were self-inflicted. They claimed he used perfume to create the “heavenly” odors, and that he was possessed by the Devil and having illicit relationships with his “spiritual daughters.”

The accusations—and jealousy— spread to the Vatican. In 1922, the Church clamped down: Padre Pio could no longer hear confessions, see his spiritual children, answer any correspondence, or say the Mass, except at irregular times and later, only in private. The Church issued statements denying the spiritual origin of the stigmata.

Thus began the years of what Padre Pio called his “imprisonment,” a trial he offered as a sacrifice to God for the needs of the “unsaved.” During his imprisonment, he spent his free time in prayer and silent communion with God, and also studied the Scriptures and the writings of the Church Fathers. Not until 1933 were all of the restrictions lifted.

The world discovers Padre Pio

World War II opened up Padre Pio’s ministry to the world. Between 1943 and 1945, hundreds of Allied soldiers stationed in southern Italy visited San Giovanni Rotundo to meet the man who bore the wounds of Christ.

Inspired by his sanctity and mystical celebration of the Mass, Catholics and Protestants alike came to revere Padre Pio. To the shock and dismay of his fellow monks, Padre Pio often administered the sacraments to Protestant soldiers and never pressed anyone to convert.

“The sick person is Christ”

Service men and women took news of Padre Pio home with them. Soon after, pilgrims and donations began pouring into San Giovanni Rotundo. These funds enabled Padre Pio to bring to fruition a project dear to his heart, the construction of a hospital: The House for the Relief of Suffering, or Casa as it was called, which opened May 5, 1956.

Padre Pio conceived of the Casa as a place where the sick would be treated in ideal circumstances, both material and spiritual, for them to open to the grace of God. He dismissed those who thought the Casa was too luxurious. He would say: “the sick person is Jesus, and doing everything for our Lord is doing little.”

Today, the Casa is one of the largest and best-equipped hospitals in Italy. It is also the international center for over 2000 Padre Pio prayer groups with more than 200,000 members worldwide.

“God’s judgment is not man’s judgment.”

Jealous of Padre Pio’s success and determined to get control of Casa funds, his superiors in the Capuchin Order soon instigated a new wave of persecution: Padre Pio’s incoming mail was opened; his conversations in the confessional and friary guest rooms were secretly recorded; and his reputation was besmirched through a successful smear campaign.

In 1961, a Vatican investigation brought new restrictions: Padre Pio could not go outside the friary; his access to the faithful was strictly regulated; and the time of his Mass had to vary from day to day.

Before his death, Pope Pius XII had granted Padre Pio a special dispensation—title to all Casa property and administrative control of the hospital. However, the new pope, John XXIII, reversed this dispensation and ordered Padre Pio to sign over the Casa to the Vatican.

Not until 1964, and the ascendance of Pope Paul VI, was Padre Pio released from all restrictions. In spite of these injustices, his inner joy was untouched. Without blame or judgment he said simply, “God’s judgment is not man’s judgment.”

The stigmata disappear

As he approached his 80th birthday, Padre Pio’s health began to deteriorate. Though confined to a wheelchair, he continued to say Mass, hear fifty confessions a day, and receive over 5,000 letters each month.

For more than a year the stigmata had begun to vanish. When he passed away peacefully on September 23, 1968, three days after the fiftieth anniversary of the stigmata, the wounds had completely healed.

John Lenti, a minister and long-time Ananda Village resident, serves at Ananda Sangha.