Let me be Christian, Jew, Hindu, Buddhist, Mohammedan, or Sufi: I care not what be my religion, race, creed, or color, if only I can win my way to Thee! But let me be none of these if that identity enmeshes me in an enclosing net of religious or social formalities. Let me travel the royal high road of realization which leads to Thee. If I am traveling on some bypath of religion, lead me onto the one common highway of realization which leads straight to Thee.

Send me the sunshine of Thy wisdom, that it lead me to the morning of my growing powers; and send me the moon of Thy mercy to guide me rightly, if ever I am lost in the dark night of sorrow.

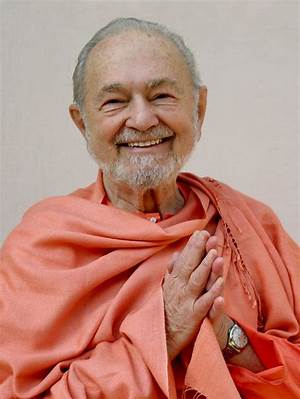

– Paramhansa Yogananda

The Teachings of Pantajali

Sutra One: Now begins the subject of Yoga.

Thus begins the only book on yoga that is universally recognized as a scripture. It was written by a great master of spirituality who lived thousands of years ago. Almost nothing is known about him. He is believed to have been married, and he lived, obviously, in India. The rest is, as far as I know, obscure. The particularly difficult aspect of his teaching, however, for us living today, is that his explanations were so condensed as to be almost incomprehensible!

These days, we like words and use them expansively. Adjectives and adverbs are the very entre and dessert of present-day writing. If a writer can tell us that a certain scene included a sunset, he won’t miss the chance. If he can describe that sunset as “glowing, multi-hued, radiant,” etc., and tell us that he himself was “transformed, tranquil, peaceful, and suffused with happiness” while watching it, he will almost certainly do so.

The spiritual teacher in India thousands of years ago would have considered the sunset itself quite irrelevant, related as it was to mere sensory knowledge, and just another aspect, therefore, of the delusion he wanted his students to transcend.

Patanjali, for most people our times, reads rather like a shopping list! And yet his is the only yoga scripture on which everyone looks as authoritative. For the modern reader, his succinctness can be exasperating!

Fortunately, Paramhansa Yogananda, a modern master, had the same profound insight as Patanjali. All liberated masters have attained the same level of realization, however much their followers may squabble about their relative merits. Yogananda explained Patanjali’s teachings with simple clarity.

There is a widely circulated printing of classes my Guru gave on the subject, but those classes were sometimes confusing, for he often departed from his subject to address particular questions in the minds of his audience. The essence of all he taught, however, includes Patanjali’s teachings. Moreover, he spent many hours with me alone in the desert, discussing the finer points of those teachings.

What I present here are not my own thoughts, but those of my Guru.

“Now comes the subject of Yoga.” That word, “now,” contains the essential meaning of this sutra, or verse. It implies that, in order to learn about yoga, one must first be schooled in the principles of Shankya. One must, in other words, be aware of the need for understanding the universal importance of the consciousness which yoga practice will provide.

The teachings of shankhya are equally ancient. In them, the true nature of human life is explained: not the day-by-day life we all live, with the need for breakfast, lunch, and dinner; the need to work in order to support oneself; the urge most people feel for marriage, for sex, for the satisfaction of producing and having children; the need for pleasure which most people find in possessions, in others’ esteem, in sensory indulgence, and in self-reassurance.

What the shankhya teaching points out is that no fulfillment can ever be long lasting. Too many fulfillments, moreover, require a commitment of energy that binds one to an ever-turning wheel. Every fulfillment is followed by disappointment; every success, by failure; every triumph, by some kind of disaster. It is like a children’s playground swing: every movement forward must be followed by an equal swing backward.

The farther the swing moves forward, moreover, the farther it must swing back in the opposite direction. The greater the outer fulfillment, the greater also the outer disappointment. One’s happiest moments are balanced by the most miserable. If one is lucky—that is to say, if one’s karma is good—his happiest moments will result all the sooner in his most miserable.

The very afternoon of the day on which he received his long-awaited promotion, for example, he will learn that he has cancer. Usually, however, his karma will be inter-mixed, and complex. His cancer will be discovered years later and will be attributed to some completely unrelated cause.

People go bumping on through life, never understanding why anything happens to them, priding themselves for the wrong reasons.

Thus, people go bumping on through life, never understanding why anything happens to them, priding themselves for the wrong reasons, and blaming others for every misfortune or moment of unhappiness when every misfortune was really brought on by themselves.

The nature of unhappiness is that it makes one think his misery will never end. It does end, of course, and because there is always light at the end of the tunnel, people always reach out for it in hope—the one ill preserved by Pandora when she closed her box.

“Get away,” Krishna cries in the Bhagavad Gita, “from My ocean of suffering and misery!”

Ordinary human beings are spiritually blind. In their ignorance of the insights of wisdom, they blame God. To them, God is cruel, indifferent, angry with people for embracing error, and coldly callous to their inevitable suffering.

One wonders why people continue clinging to the wheel. But the answer is obvious: there is always hope! They have known enjoyment and success: perhaps they will know these things again. And so they do, of course. They cling to the wheel by choice. The clinging is not God’s wish for them.

Shankya tell us why we should get off the wheel. Clinging can get us nowhere. It could not possibly do so.

The deeper “why” of it, however, is not explained. A saying of shankya is, “Ishwar ashiddha, God is not proved”—the point not being that God doesn’t exist, but rather that knowledge of the world through the senses cannot prove His existence. Shankya is directed toward proving that sensory knowledge is inadequate for any true understanding. (The labors of science are therefore, in essence, futile!)

Elsewhere in the Indian teachings, it is made clear that what we call God is, in fact, Infinite Consciousness. That Consciousness, the Supreme Spirit, is without substance, and without movement of any kind. Its nature is Satchidananda: ever-existing, ever-conscious, ever-new Bliss. The “ever-newness” of that state inspires it from time to time to manifest part of Itself as Cosmic Creation. This it does by setting Itself superficially—at the surface, so to speak, of the Infinite Ocean of Awareness—in motion.

The Christian New Testament, the Gospel of St. John, begins with the sentence, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” The meaning of this sentence is no different from what I have already written. The word of a man is the vibration of his consciousness. And the Word of God is the Divine Consciousness, vibrating. Truth, whether East or West, cannot but be the same. The Cosmic Vibration, AUM, is what the Bible calls the Holy Ghost.

In Christian tradition we learn of the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost; three in one and one in three. The mystery seems impossible of solution. But it is explained quite simply in the Hindu tradition—as simply as anything cosmic can be explained in human terms!

In Christian tradition we learn of the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost; three in one and one in three. The mystery seems impossible of solution. But it is explained quite simply in the Hindu tradition—as simply as anything cosmic can be explained in human terms!

God the Father is the Supreme Spirit: Sat. God the Holy Ghost is AUM. The Son is not Jesus Christ, but the Christ Consciousness, Sat, or the Kutastha Chaitanya: the unmoving consciousness of Spirit reflected (so to speak) in every point of Creation. For there cannot be two infinite realities.

The vibration necessary to produce Creation cannot then exist as a separate reality from that of the ever-motionless Spirit. In that vibration itself there would have to exist also motionlessness. And so it does. For at the central point, between each oppositional movement, there would have to be a point of rest where those opposites cease to exist. That point of rest is the “reflection” of the state of stillness beyond Creation: of the Supreme Spirit itself. This still reflection is the Christ Consciousness—Tat, in the Sanskrit terminology. Thus, we have the three in one and one in three!

Jesus, the man, was not the “son of God.” But in meditative awareness, he had that oneness with the Christ consciousness. He himself (be it noted) used both expressions: son of man, and Son of God. It was in that higher state that he could say rightly, “I and my Father are one.”

By his example, and also by the example of all who, by perfect inner stillness and purity, have attained that high state of consciousness, we may all be aware that we are, all of us, products of God’s consciousness. All the talk in the churches about our being the children of Adam and Eve and born in sin is itself a sin! Sin means only error: it means to think we can find fulfillment in acts and attitudes that will keep us bound to what is in fact but a delusion: this worldly existence. It is all a dream. It has no real form, substance, or reality of any kind, except as God’s dream! Our greatest sins are only mistakes, committed in misunderstanding. We may sin, but we ourselves are not sinners. No sin can define our reality. A saint, Yogananda used to say, is a sinner who never gave up!